There’s this thing in zen practice about work.

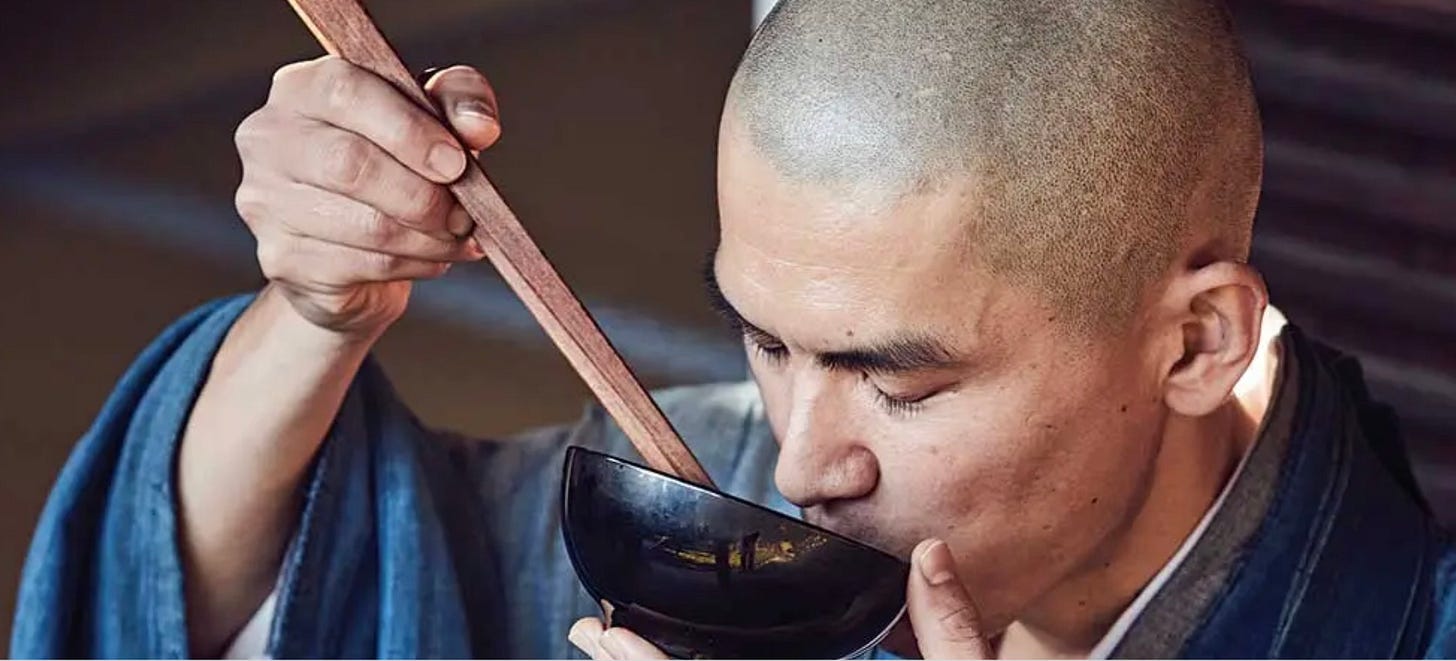

It’s romantic imagery, a series of zen cliches: a monk, head shaven, silently and carefully—reverently—polishing the temple floor, cutting a board, slicing carrots, pulling weeds, clearing brush, sewing a robe, lighting incense, sweeping the temple courtyard.

They’re well-earned cliches. Several hours each day in Sesshin, during Training Periods, and during Interim Periods, are spent in work practice—to maintain the physical integrity of the monastery (or zen center, or temple), to feed the residents and visitors, to simply keep things clean, and just because it has to be done. Taking care of the center (and by connection, everyone at the center) is taking care of practice, after all. It’s not like there’s practice aside from what’s urgent right now, and zen is all about what’s happening right now. Zen students often take absurd pride in work practice—cleaning the bathrooms, in the context of sesshin, is a perversely elegant job assignment. Some people want to work in the kitchen. Some folks want to clear brush (there’s chainsaws). There’s cutthroat competition to empty the compost pails and mop the kitchen floor. The grittier the work, the more it feeds into the vibe of zen practice.

Work practice is also a reminder: our work as students doesn’t begin and end on the cushion. Everything we do is practice. The doing of the work is actualizing practice as our lives. What’s more urgent than doing what has to be done, right now? What’s the thread running through our lives? What else is there to living, aside from whatever it is we’re actually doing?

Traditionally, at a zen monastery, the Tenzo (temple head chef) is a seasoned practitioner, often second only to the Abbott in seniority. The Tenzo’s literal responsibility is maintaining the life and practice of the community. What’s more important than that?

In Eihei Dogen’s essay Instructions for the Cook (Japanese: Tenzo Kyokun), Dogen stitches together a pair of encounters he had during his stay in China, in the early 13th century.

In the first encounter, at a monastery on Mt. Tendo, Dogen sees the Tenzo outside drying mushrooms. It’s a very hot day: an old monk, the Tenzo is bent with age, and supporting himself on a bamboo pole, no hat to keep the relentless sun off his shaved head.

“Tenzo,” Dogen asks, “how old are you?”

“68.”

“Couldn’t someone younger be doing this work?”

“Others are not me.”

“Tenzo,” Dogen asks, pressing the old monk, “Couldn’t you do it later?”

Looking up from his work and holding Dogen’s gaze, smiling, the Tenzo replies, “what time exactly should I wait for?”

In the second encounter, while Dogen was waiting for permission to enter China (13th-century immigration problems—some things never change), and still on board ship, an aged Tenzo comes on board to buy mushrooms. Dogen strikes up a conversation with the older monk, and it turns out he’s walked 12 miles to secure these particular mushrooms for a festival meal. Dogen offers the monk dinner, but the older monk demurs, saying he has to get back to the monastery or the temple meal that night won’t go well.

“Tenzo,” Dogen asks, “Aren’t there assistants who know how to prepare the meal for you? It’s 12 miles back to the monastery.”

“My practice,” the older monk says, “is Tenzo. How can I leave my practice to anyone else?”

“At your age,” Dogen persists, “why work as Tenzo at all? Why not devote yourself to zazen and koan study?”

“My friend,” the monk replies, “I don’t think you really get this whole practice thing.”

One way to look at Dogen’s writings—and it’s a very dense, demanding (and beautiful) set of writings—is to look at everything as Koan. There’s two right here: “what time exactly should I wait for?” and “how can I leave my practice to anyone else?” What am I taking full responsibility for right now?

There’s this thing in zen practice about work.

So many koans revolve around work. Here’s another one, this time Case 21 from the Book of Equanimity (taken from Gerry Shishin Wick Roshi’s translation):

Main Case

‘Attention! As Ungan was sweeping the ground, Dogo said “you’re hard at it!” Ungan replied “You should know there’s one who isn’t hard at it.” Dogo said, “So, is there a second moon?” Ungan held up the broom, saying, “Which moon is this?” Dogo desisted. Regarding this, Gensha remarked, “Indeed, this is the second moon.” Ummon also said, “the butler watches the maid politely.”’

The first line of the Appreciatory Verse is:

“Using what’s at hand he finished up the yard.”

There’s a lot of layers here, but just to limit the scope right now to the sweeping, and that first line of verse—in the simplest, clearest way, this is a koan about work, right? Ungan’s sweeping the ground. He could be slicing vegetables, or drying mushrooms. Hard work, to be sure, and calling back to that zen cliche, that monk doing their zen thing. Sewing a robe. In this case, sweeping. Dogo and Ungan testing each other, pushing their understanding.

Of sweeping? Sure, sweeping. One thing I’ve learned about koans: they’re not metaphors.

If Ungan’s sweeping’s not a metaphor, what is it? It’s sweeping. It’s polishing the floor. Ungan’s sweeping is cutting a board, slicing carrots, pulling weeds, clearing brush, lighting incense. He’s drying mushrooms. Ungan’s sweeping is sweeping the temple courtyard. Using what’s at hand he finished up the yard. That’s what he’s up to: he’s sweeping.

What do we understand about sweeping—what do we understand about work? ‘You should know there’s one who’s not hard at it.’ And as Dogo says, ‘You’re hard at it.’ Which is it? Is sweeping the ground hard or easy? is work hard or easy? Is the broom a second moon? How many moons do we have?

There’s just the one moon. And the broom. And Ungan’s sweeping. Sometimes sweeping’s hard, and sometimes sweeping’s easy. It’s just sweeping. It’s just taking care of practice.

Just the one Tenzo drying mushrooms. Just the one Tenzo walking 24 miles to get the right mushrooms for a festival dinner. Others are not me. Taking responsibility for this moment: drying mushrooms, sweeping the ground. Taking responsibility for this life. If not now, Ungan’s sweeping is expressing, when?

There’s a thread to follow. This sweeping, this drying mushrooms, this taking responsibility. It’s not limited to zen practice.

Ungan’s sweeping and Dogen’s Tenzos echo in: ‘If not me, then who? If not now, when?’ a phrase from the Jewish tradition, paraphrased from the Talmud, and attributed to Hillel the Elder, from the 1st Century CE. There’s great stress in the Talmudic tradition on taking personal responsibility for your life—directives on how to expend agency over your intentions, over your behavior. Hillel’s imperative is to interrogate this life. What is it we’re doing? It’s your life to own, or not. Hillel passionately wants to stress that ownership. He demands attention to the details of living. What life are we stitching together. Hillel’s on the same page as the tenzos, no different than Ungan.

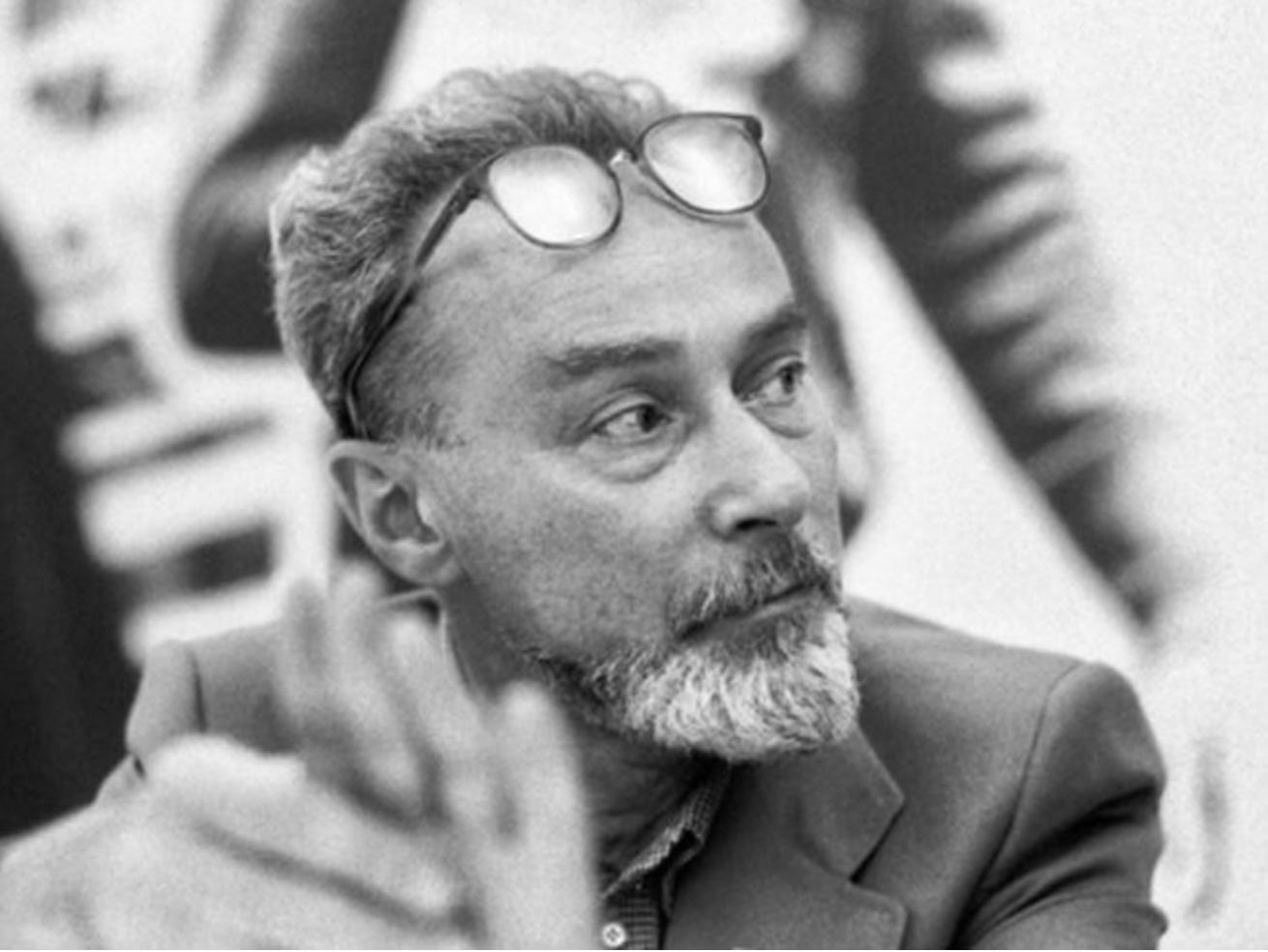

Let’s keep following that same thread. Hillel’s phrase shows up as the title of ‘If Not Now, When?’ by the Italian novelist Primo Levi, about Jewish partisans in Eastern Europe during the Second World War. Levi, a Holocaust survivor, is a ruthless poet of survival and the responsibility of the living, of the survivor—he’s always asking: how do we stand up in the face of whatever’s right in front of us? How do we take responsibility for the life we’re handed? Levi’s project as a writer is always perched on the precipice. He starts where life is at its most undeniably urgent. There’s no raising stakes for him as a writer: his lived experience pushed him to the absolute limits of his humanity, and his writing lives in that space. Every moment, everything Levi gives attention to—the stakes are life and death. Living stripped to its barest essential. Life, or death? What do you do?

These are the stakes of living. We’re all going to die. Right now, in the face of that, how do we live?

How high are the stakes of practice? How high are the stakes of our lives?

A 13th-century Japanese zen monk, two 13-century Chinese zen monks, a first-century Jewish theologian, a 20th-century Italian novelist. All pointing to the same thing. In some way, all talking about sweeping. All asking us to engage with the urgency of this moment, this life we have. Whatever that life is. Whatever robe we’re sewing.

The contemporary Korean Zen Monk Jeon Kwon, who’s been featured on Netflix’s hypnotic meditation on cooking, chefs, and food, Chef’s Table, might as well be one of those Tenzo’s from Dogen’s Instructions for the Cook. Watching her work, in her attention to detail, to the care she takes with each ingredient, the way she manages the temple garden—down to the way she speaks—she’s expressing a kind of devotion, a reverence for doing. She crystallizes that focus Dogen’s Tenzos embody, that absolute simplicity of Levi’s no-choiceness. In her gentleness, her lightly held attention, in the way her hands dance with a knife and a carrot, or the way she slices a mushroom, she’s expressing her life. Expressing reverence for what she has right in front of her. There’s no division between what she’s doing and who she is; no division between action and expression. In her exquisitely refined attention, in her care, she’s totally present. She’s completely alive in every gesture, in every moment. What a gift. What a lovely teaching. What beautiful sweeping.

Ungan’s sweeping the temple grounds—stitching a robe. Reckoning with this moment. You won’t find a more concrete zen directive than that, right? What’s happening right now? What do I do in this moment, how do I treat this life? What’s my work? How do I sweep? How do I handle the broom?

There’s this thing in zen practice about work.

What’s the work of this moment? Ungan’s sweeping the ground. There you go: keep sweeping.

If you find keep sweeping useful and/or interesting, and it’s for you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe.

Feel free to share keep sweeping. The more, the merrier.

Your comments and thoughts are always welcomed, and encouraged. Love to hear what you think!

One more thing.

As a zen priest, I’m a student of Tenshin Fletcher Roshi at Yokoji Zen Mountain Center. For more info on Yokoji, please visit www.zmc.org.

I’m also the caretaker of Warwick Zendo, a small in-person and online sangha based in the lower Hudson Valley of New York. if you’d like to check out our practice community, we’re at www.warwickzen.org. How this works.

I plan to post at least once a week, at minimum. The Freeside will offer those weekly posts, which will disappear behind the Payside wall after two weeks. Payside opens access to all the archived posts, and will also (eventually) offer access to some longer writing and ongoing investigations into practices both literary and zen.

Payside also helps to sustain this project, and this practice. Like any creative project, keep sweeping is a kind of labor, and as such, your support to sustain that labor is much appreciated.

If Payside is not for you, that’s all good. The posts will keep coming on Freeside. The support of your reading and attention is a deeply appreciated gift, and I thank you for being here.

You won’t have to worry about missing anything. Every new edition of the newsletter goes directly to your inbox.

I love this paragraph - Work practice is also a reminder: our work as students doesn’t begin and end on the cushion. Everything we do is practice. The doing of the work is actualizing practice as our lives. What’s more urgent than doing what has to be done, right now? What’s the thread running through our lives? What else is there to living, aside from whatever it is we’re actually doing? - As a parent, a mother, there is lot of unseen work which is most urgent and present. A lifelong thread one could say. It’s often seen at odds with the spiritual life, but I feel it is at the heart of presence, compassion and practice.